Coaching “the Recovery” – by Howard Aiken

(This is the fourth in a series of coaching notes and is probably best read with the preceding “Coaching the Finish”. The techniques described apply primarily to rowing rather than sculling and to bigger boats rather than small ones).

The Recovery should be easy, surely? We’ve done the hard work on the drive. We’ve got the spoon out of the water at the finish and we’re on our way back to the catch. What is there to coach on the recovery?

Well here’s the thing. While it might take a trained eye to spot if your catch, drive or finish is good, anyone can judge the quality of a crew from their recovery. Good crews make it look easy. All the spoons leave the water together and move through the air at the same height and speed until they enter the water together at their next catch. Meanwhile their boat stays perfectly level, moving forward as if on rails.

No-so-good crews can’t do this. Their boat is off-balance and during the recovery with one side of the boat higher than the other – or one side’s blades may even be dragging across the water to the catch.

I’ve referred elsewhere to the “hierarchy of needs” within a boat, namely Timing, Balance and Power – in that order, with timing being the fundamental requirement, balance being built on good timing and power being useful only if the other two are in place. Clearly there is no power component to the recovery, so it is mainly about timing and balance.

First, however, let’s look at the sequence of movements which make up the recovery:

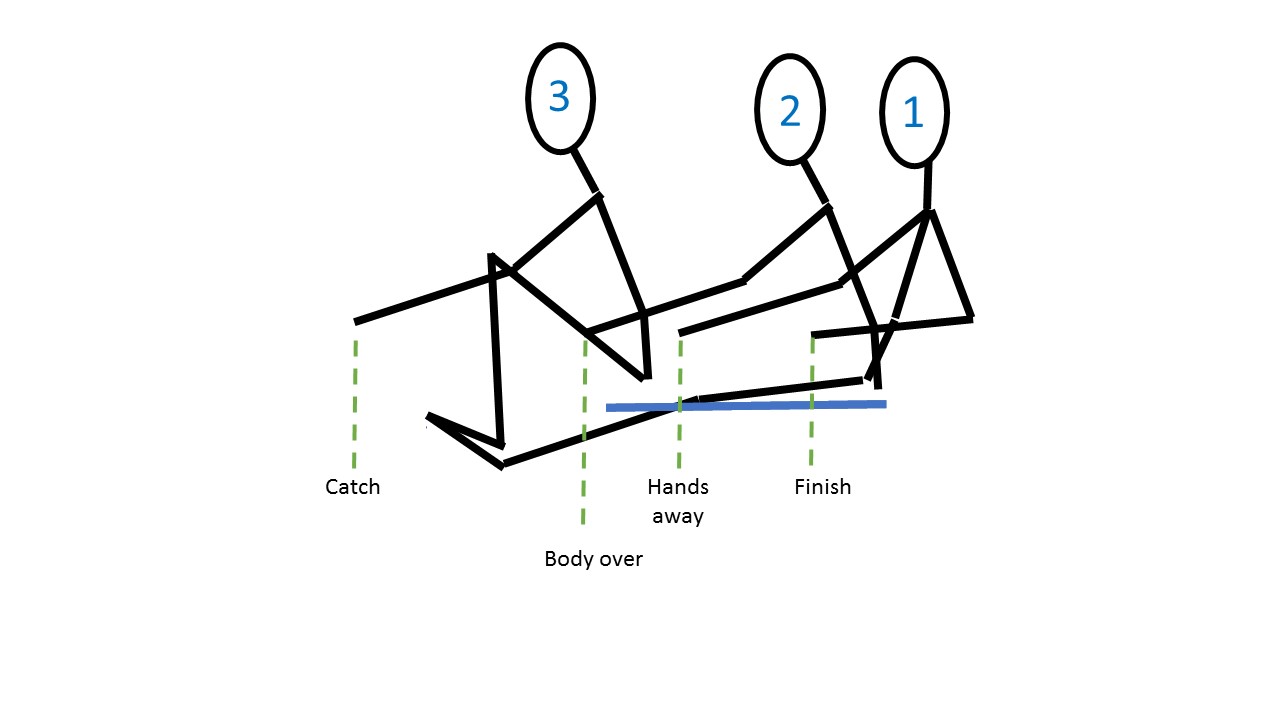

Figure 1 Stick diagram showing the rowing recovery sequence

The recovery begins as the spoon is lifted from the water at the Finish (1). Before the body moves, the hands push away horizontally until the arms are fully extended at “Hands away”. The hands then pull the body over (2), the trunk pivoting at the hip while the slide remains at backstops. Only once the forward reach with the arms and the forward lean with the body are established, should the slide begin to move toward frontstops. As the slide moves, the upper body and arms should be perfectly still, the head high, the core active, the legs flexing at the knees and hips until the body arrives at frontstops and the spoon is dropped into the water at the catch (3).

Rowers sometimes need reminding that the catch should be a single contact between the squared blade and the water. Any contact between blade and water between the finish and the catch is bad, because the drag caused by a blade in or on the water is hundreds of times higher than the drag of the blade in air. Rowers should hate the sound of blades dragging on the water, because that sound is the sound of energy and speed bleeding from the boat. In a well-rowed boat, the recovery phase of the stroke should be silent except for the sound of the moving slides and the water flowing around the hull.

Timing the recovery for most rowers is less about when it starts than how fast it moves. Novice rowers particularly tend to rush the recovery, lunging forward into frontstops in their haste to get on with the next stroke. Part of the problem is that novice rowers frequently lack the fine control in their knee flexor muscles required to deliver a smooth recovery. Untrained or weak knee flexors tend to produce an uncontrolled twitch rather than a smooth contraction, so it can be surprisingly difficult for novice rowers to slow their progress up the slide. Many coaches will be familiar with the fact that it is often the weakest rower who is fastest on the recovery and so either catches early or is obliged to wait at frontstops for the rest of the crew to catch up.

Different coaches will sometimes say apparently contradictory things about slide speed on the recovery. As a rower I have been coached (by different coaches and at different times) to decelerate into frontstops in order to avoid checking the forward motion of the boat and to accelerate into frontstops to raise the bows slightly for the next stroke. My own view is that the greater contribution to boat speed is the deceleration into front stops. The reasons for this are unambiguous but perhaps not explained to rowers as often or as clearly as thy should be. During the recovery, the crew – who collectively weigh much more than the boat they are rowing, are moving in the opposite direction to the boat. If they hit frontstops hard, their collective inertia results in sharp deceleration of the boat. This can be seen in a sudden dip of the stern into the water, or in coxed boats, the involuntary pitching forward of the cox’s head and upper body. We call this error “stern check” and there is an interesting coaching trick for monitoring it here .

A useful cue for both rowers and coaches working on slide speed is the sound of the wheels on the runners during the recovery. If the rowers are accelerating into frontstops the wheels will sound a rising note. If they are decelerating, the wheels will sound a falling note – and if you can get the crew to produce that falling note you will get a gentler arrival at frontstops and less stern-check.

I’ve never coached acceleration into frontstops myself, but it is not quite as contradictory as it might seem. From my experience as a rower, the coach was not asking us to crash into frontstops. What he was asking for was a slight acceleration right at the end of the recovery and immediately before the catch. Understanding the reasons for this requires a short digression into very basic Newtonian mechanics.

At the end of the drive phase the crew are at backstops and moving at the same speed as their boat. As they begin the recovery, moving in the opposite direction to the boat, some of their kinetic energy is transferred from their bodies to the boat. As a result, the boat accelerates after the spoons leave the water (you can also think of this as the rowers pulling the boat forward toward their bodies with their feet). So the theory behind the deliberate acceleration into frontstops over the last few centimetres of the recovery is to accelerate the boat slightly before the catch. And the catch must go in milliseconds after that acceleration to keep the boat moving.

Whether it works in terms of producing additional boat speed I can’t say – which is why I don’t coach this technique myself, but evidently some coaches believe it does.

The last thing to say about timing is that the slide is only part of the story. In a good crew, not just the slides, but the hands and the heads will all be moving together, all following the rower in the stroke seat. This does not happen by accident, the crew have to work at it quite deliberately. And as no two occupants of the stroke seat will move in exactly the same way, the crew must adapt their timing every time the occupant of the stroke seat changes.

Balance in the recovery is one of the most challenging aspects of rowing for many average club or college rowers but at the same time is the most obvious characteristic of a competent crew. In normal rowing a crew should be spending two or three times longer on the recovery than on the drive and there is a vast difference in efficiency between a boat which, on each recovery, drags half its blades across the water and the efficiency of a boat which is balanced, with all its blades moving at the same height above the water.

The most important point to make about balance in the recovery is that it originates in the drive and finish of the previous stroke. Balance is set up during the drive and inherited by the recovery. If the boat was balanced at the finish of the previous stroke, that balance must be maintained during the recovery and into the catch. If the boat was off balance at the finish of the previous stroke, the boat must be rebalanced during the recovery – a more difficult task.

Maintaining balance is all about minimizing unwanted upper body movement – particularly sideways (lateral) movement. This is best achieved by using “core stability”, activating the muscles of the trunk by sitting up tall and pulling the stomach in slightly. The upper body position we need can be described as eyes front, heads up, shoulders down and chests out. This needs to be maintained throughout the stroke, not just on the recovery.

As with slide speed, coaches differ in their views on sideways movement. My preference is to coach crews to keep their weight on the centreline of the boat throughout the stroke. Seen from in front or behind, their heads should remain in line while their arms follow the arc of the blade’s handle. Other coaches will have the heads following the same arc as the arms, so that at frontstops the bowside and strokeside heads form two distinct rows. I’ve even seen rowers who have evidently been coached to lean toward the rigger during the drive and then return to the centreline on the recovery, producing a rather odd rotary motion. All of these can work, but keeping heads in the midline is simplest, particularly if crew members differ in height or weight. Also, the more asymmetric the technique, the greater the obstacles faced by rowers changing from one side of the boat to the other, something I feel strongly that all rowers (and particularly young rowers) should do regularly.

Recovering balance on the recovery can be challenging, which is why in a previous blog I emphasised the importance of keeping the boat balanced at the finish. If the boat is badly off balance at the finish, a novice crew stands very little chance of correcting it on the recovery. However, a slight imbalance can be corrected during the recovery if the crew has good core stability. This can be augmented if required (and if the crew has been coached in the technique) by the use of foot pressure. This works exactly as one might expect, with a dab of pressure on the rising side of the boat serving to stop it from rising too far. This is however a fairly advanced technique and in practice limited to fine-tuning the balance, not correcting gross errors.

In conclusion, the recovery is the phase of the rowing stroke which tells the world about the technical capabilities of your crew. A crew which can maintain the balance of their boat during the recovery with all their blades in the air, has the best possible platform for the efficient translation of power into speed. A crew which is unbalanced – or worse, drags blades across the water, are going to be handicapped by a less stable and less efficient boat.